Charting the Past and Future Transformations of our Housing Infrastructure

By George Gantz, for Long Now Boston, September 12, 2018

While we often think of cities in terms of skylines, business activity and public buildings or monuments, their primary function is the housing of people. The patterns and forms of that housing are critical to the life of a city, and they reflect a complex interplay of demographics, economics, public policies, cultural aspirations and aesthetics. At the Long Now Boston Conversation on September 10, 2018, three of Boston’s top planners and architects helped unpack this complexity. They served up a history of past transformations, as well as a vision for a pending renewal, of Boston’s housing infrastructure. The most important hallmarks of success seem to be: resilience and flexibility in the face of change; the support of deep and diverse social interaction; and the commitments needed to provide and maintain the public infrastructure.

Booms and Busts

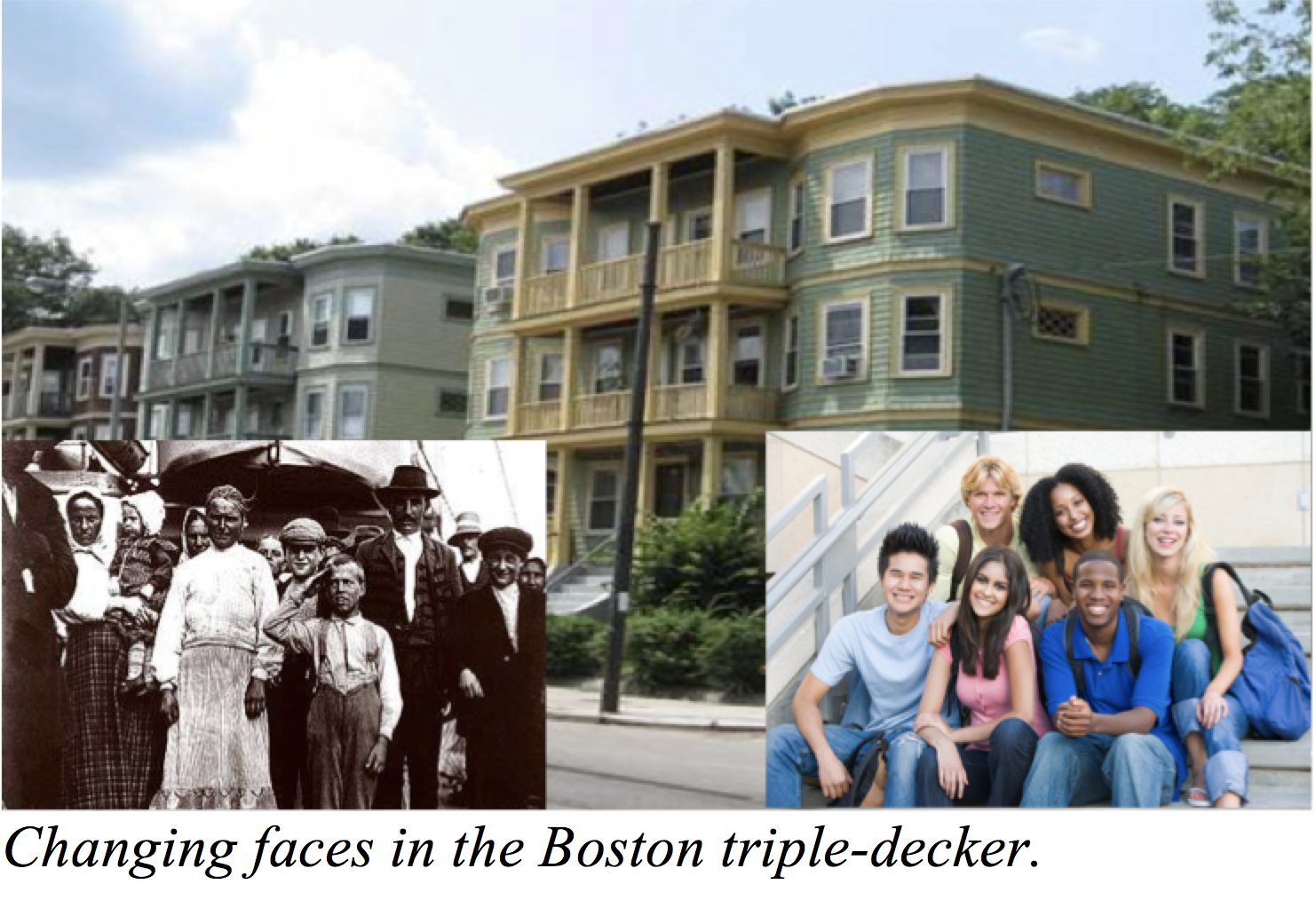

Barry Bluestone, Professor at Northeastern University, offered a concise history of key housing transformations in Boston. In the 50 years from 1870-1920, the continuing wave of immigration tripled the city’s population, as desperate settlers sought opportunities in the region’s expanding industrial and commercial industries. The response to this demand was a new technology – the triple-decker. These homes provided a cost-effective opportunity for those who succeeded early to own a house big enough for newly immigrating relatives or rent-paying tenants. The triple-decker is a ubiquitous feature of many Boston neighborhoods, and continues to play an important role in the housing infrastructure of Boston more than a century later.

Boston’s fortunes took a turn for the worse in the post-WW2 period of 1950-1980 as the burgeoning middle class began moving their young families to the promised land of the suburbs. Facilitated by improved roads, highways and the automobile, as well as the new technology of tract development, each aspiring family could afford a home of their own, along with a “car in every garage”. Boston’s population dropped by almost a third as its middle class hollowed out. Some suburbs doubled or tripled in population with the influx of wealthier families.

Boston began to recover steadily after 1980, supported by growth in two key demographics – older people whose children had grown up – and younger people who had no children. This trend has continued. In the first decade of the 21stcentury, 20-34 year olds accounted for nearly three-quarters of Boston’s population growth. Interestingly, many in this younger population have been moving into triple-deckers, by two paths. Gentrification occurs when young, higher-income professionals in search of city housing squeeze out working families. The transient student population, and others with limited means, find it economical to share an apartment with several others.

Since new housing is scarce, the rapidly increasing demand has had the inevitable effect of driving up rents and real estate prices. The median price of two-unit and three-unit houses has more than doubled since 2009 and rents are up 60%. The demographic trends of increasing millennial and older populations are expected to continue for at least the next 15 years. The problems in Boston are not going away.

As a consequence, Boston now suffers from a seriously depleted middle class and a high level of income disparity, as well as many neighborhoods that are more segregated than they were a generation ago. This is not a surprise to anyone, and these concerns are getting a lot of attention in the development and architectural community, as well as in the administration of Boston Mayor Marty Walsh. Just as the triple-deckers of the late 1900’s have shaped Boston’s housing landscape for the past 100 years, how these institutions respond now may well shape Boston’s housing landscape for the next 100 years.

Broadening the Perspective

Peter Rose, of Peter Rose and Partners, has worked on development projects around the globe, and he offered some insights about the range of factors that come into play in the life and death of city infrastructure. He noted, for example, that the factories of Detroit won WW2 for the United States. After the war, the City was rewarded with an economic boom fueled by the explosion in the demand for automobiles produced in refurbished war factories. Detroit became “Motor City”, and for a time was one of the richest cities on the planet. Unable to re-position itself in response to globalization and the decline in US manufacturing later in the 20thcentury, Detroit’s population and economic activity collapsed. Yet, there are even now signs of resurgence in post-bankrupt Detroit.

Montreal provides another example of resurgence, one that Peter contributed to directly. Montreal traditionally was a “poor” city, but an important port for Canada. In 1976, in response to increasingly containerized shipping requiring larger facilities, the Old Port was abandoned, and its massive granaries were largely demolished and forgotten. In this period, Montreal also suffered a significant decline in population and economic activity, in part as a result of Quebec’s succession effort. Peter and his team were hired to conduct the necessary studies and to plan for the re-invention of the Old Port, which was accomplished in the early 1990’s. It is now a recreational and historical area that draws six million tourists annually, and is described in Wikipedia as “a cultural gem and a major tourist attraction, having been enhanced with museums, restaurants, shops and water-related activities.”

The keys to this successful rehabilitation included the careful integration of data and design considerations for all of the key infrastructure including mass transit, roads, energy, recreation, housing, retail and aesthetics. They discovered that the immense foundations for the destroyed granaries could be re-used and the abandoned canal could be re-purposed for recreation and aesthetics, and they deployed creative lighting to feature the interesting architecture of older structures. The Metro (subway line) became the key transportation corridor, with the surface oriented to human activities.

Peter emphasized the significant importance of mobility considerations, and specifically the benefits of high volume public subways and a de-emphasis of cars, to the emergence of high-quality, human-friendly city neighborhoods. He noted, in irony, that the last significant addition to the Boston Subway system was in 1928. The “T” system is antiquated and incredibly slow, as a visit to any modern European or Asian city makes readily apparent. While the billions for major subway upgrades may seem daunting, Montreal demonstrates the very long-term benefit to the health of neighborhoods and economic productivity for a city the size of Boston. Good planning for Boston should include a complete re-think of its public transit.

In addition, good urban planning and design requires the careful study and balancing of many factors. This effort requires leadership, support and commitment from administrative authorities (government) and a collaborative process among urban planners, architects, developers and community groups. Cities where these factors are absent will struggle.

Micro Considerations

Tamara Roy, an architect with Stantec in Boston, studied architecture with her husband in Amsterdam, where they were exposed to some of the best teachers and to a living experience in “micro-housing.” Their 1-bedroon living unit was only 280sf, including bath, kitchen and living room. However, with easy access to the amenities of a great city by foot, bicycle and public transit, they did not find it to be a hardship – in fact, it simplified life. They once hosted a Thanksgiving Dinner (an unknown tradition to their fellow students and friends) for 30 in their apartment, and later in their stay, added a baby to the mix. This experience helped shape Tamara’s appreciation for the opportunity that micro housing provides for more affordable yet pleasant higher-density housing solutions.

This opportunity is particularly valuable in the context of escalating rents and the high-demand for housing for a younger demographic, including students, in many of our more attractive cities, including Boston. Tamara noted that the average rent for a studio or 1-bedroom apartments in the newer high-rise apartment buildings she has worked on in Boston averages from $2,000 to more than $3,500 per month. She contrasted the design features of market rate housing in Boston to those of the “Tree House,” a new high-rise dormitory built for the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. The Tree House employs group suites and common facilities that increase density while facilitating social interaction and reducing per occupant cost significantly. As a LEED Gold building, one could also say the Tree House aptly earns its name, while also dramatically reducing operating costs.

Tamara is excited about the growing opportunity for micro-housing, but sanguine about the hurdles that need to be overcome. First among these is fear – the fear that one’s neighborhood will change and that micro housing will pollute, rather than enhance, the city’s character and landscape. This fear needs to be balanced against the increasingly desperate need for livable affordable housing options in our cities. More of the same will simply exacerbate the current problems, which are themselves causing negative changes in neighborhoods and cities. Under her leadership, the Boston Society of Architects developed, as a teaching tool, a sample “urban housing unit” which has been exhibited in different neighborhoods. This pre-fab 1-bedroon 385sf housing module can be built for $65,000, a small fraction of a conventional unit. In addition to filling a vital need in Boston, the building of these units for shipment to other cities could provide an employment opportunity for skilled labor. Having people be able to visit the unit is intended to reduce the fear of the unknown.

Conclusion: Managing an Uncertain Future

When asked by a questioner how all this will all affect housing in hundreds of years, Barry said, “I have no idea. But I can tell you what I think will make it better now.”

Barry envisions a “21stCentury Village” concept, focusing on the two high growth ends of the demographic spectrum in Boston – the young and the old. The goal here is to build new housing – lots of it – specifically for the smaller households and individuals that now dominate the demand for housing in Boston. This population includes graduate students, medical residents & interns, and other young professionals, as well as aging baby boomers. By housing the growing pool of millennials, this program would reduce the intense demand for the traditional triple-deckers originally designed for middle class families. By housing the growing pool of older households, this program would also reduce housing demand in the suburbs.

The basic design would be for apartment structures featuring a range of units from small/”micro” apartments to multi- bedroom units varying in affordability. There would be common shared spaces such as lounges, laundry, meeting, study and practice rooms, and offices to facilitate small business incubation. Ground floors would be designed for retail establishments and roofs for gardens and social space. Proximity to public transit is critical, along with some space for Zip Cars, bicycles and storage.

Is this realistic? As Peter observed, good development and housing solutions requires leadership, support and commitment from administrative authorities (government) and a collaborative process among planners, architects, developers and community groups. The process will need to bring all these actors together. This is a big challenge.

But Tamara expressed optimism that a consensus is emerging. The various constituencies in Boston and its neighboring towns and cities recognize that changes are needed to address these intensifying housing issues. Higher-density housing is a key part of the solution, and lower-cost, sustainable technology is available to facilitate the transformation.

21stCentury Villages, developed within the urban cityscape, may indeed provide an optimal answer to the housing issues that Boston and many other cities are facing today. We can hope that these cities are able to demonstrate the flexibility and the foresight to be able to implement this solution. In order to do so, they will need to employ a set of approaches and practices to assemble and organize the resources, the expertise and the local communities’ willingness, all of which are necessary for success.

These approaches and practices may, in fact, give us the answer to the long-term question. What does a city need to do to remain flexible and resilient in response to changing circumstances?

The truth is that housing is constantly changing, and that the complexity and uncertainty of the many forces at work make long-term forecasting very difficult. Housing change may be harder to predict than climate change. However, the real challenge is not in forecasting the future, but in learning how to appropriately shape the future. We can take steps now to improve the housing realities in the immediate future. We can learn to respond flexibly to the rapidly changing factors of economics, demographics, technology and human preferences. If we do so, we will be better able to navigate a steady course over the longer term.

Let’s get together again in ten years and hear how Boston, and other cities, have done in meeting the current housing challenges.